Pay as You Earn Taxation Economics Definition

What You'll Learn

- Discover the three basic tax types—taxes on what you earn, taxes on what you buy, and taxes on what you own.

- Learn about 12 specific taxes, four within each main category—earn: individual income taxes, corporate income taxes, payroll taxes, and capital gains taxes; buy: sales taxes, gross receipts taxes, value-added taxes, and excise taxes; and own: property taxes, tangible personal property taxes, estate and inheritance taxes, and wealth taxes.

- Develop a basic understanding of how these taxes fit together, how they impact government revenues and the economy, and where you may encounter them in your daily life.

Introduction

Most taxes can be divided into three buckets: taxes on what you earn, taxes on what you buy, and taxes on what you own.

It's important to remember that every dollar you pay in taxes starts as a dollar earned as income. One of the main differences among the tax types outlined below is the point of collection—in other words, when you pay the tax.

For example, if you earn $1,000 in a state with a flat income tax rate of 10%, $100 in income taxes should be withheld from your paycheck when you earn that income.

If, a week later, you take $100 from your remaining earnings to purchase a new smartwatch in a jurisdiction with a 5% sales tax, you'll pay an additional $5 in taxes when you purchase that item.

Altogether, $105 of your initial $1,000 in income has been collected in taxes, just not at the same time.

With that in mind, below is a brief overview of the main types of taxes you should know to be an educated taxpayer.

Taxes on What You Earn

Individual Income Taxes

An individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns.

Many individual income taxes are "progressive," meaning tax rates increase as a taxpayer's income increases, resulting in higher-earners paying a larger share of income taxes than lower-earners.

The U.S., for example, levies income tax rates ranging from 10 percent to 37 percent that kick in at specific income thresholds outlined below. The income ranges for which these rates apply are called tax brackets. All income that falls within each bracket is taxed at the corresponding rate.

| Rate | For Single Individuals, Taxable Income Over | For Married Individuals Filing Joint Returns, Taxable Income Over | For Heads of Households, Taxable Income Over |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 12% | $9,875 | $19,750 | $14,100 |

| 22% | $40,125 | $80,250 | $53,700 |

| 24% | $85,525 | $171,050 | $85,500 |

| 32% | $163,300 | $326,600 | $163,300 |

| 35% | $207,350 | $414,700 | $207,350 |

| 37% | $518,400 | $622,050 | $518,400 |

| Source: Internal Revenue Service | |||

Corporate Income Taxes

A corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits, which are revenues (what a business makes in sales) minus costs (the cost of doing business).

Businesses in U.S. broadly fall into two categories: C corporations, which pay the corporate income tax, and passthroughs—such as partnerships, S corporations, LLCs, and sole proprietorships—which "pass" their income "through" to their owner's income tax returns and pay the individual income tax.

While C corporations are required to pay the corporate income tax, the burden of the tax falls not only on the business but also on its consumers and employees through higher prices and lower wages.

Due to their negative economic effects, over time, more countries have shifted to taxing corporations at rates lower than 30 percent, including the United States, which lowered its federal corporate income tax rate to 21 percent as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

Payroll Taxes

Payroll taxes are taxes paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs. Most taxpayers will be familiar with payroll taxes from looking at their paystub at the end of each pay period, where the amount of payroll tax withheld by their employer from their income is clearly listed.

In the U.S., the largest payroll taxes are a 12.4 percent tax to fund Social Security and a 2.9 percent tax to fund Medicare, for a combined rate of 15.3 percent. Half of payroll taxes (7.65 percent) are remitted directly by employers, with the other half withheld from employees' paychecks.

Though roughly half of the payroll taxes are paid by employers, the economic burden of payroll taxes is mostly borne by workers in the form of lower wages.

Capital Gains Taxes

Capital assets generally include everything owned and used for personal purposes, pleasure, or investment, including stocks, bonds, homes, cars, jewelry, and art. Whenever one of those assets increases in value—e.g., when the price of a stock you own goes up—the result is what's called a "capital gain."

In jurisdictions with a capital gains tax, when a person "realizes" a capital gain—i.e., sells an asset that has increased in value—they pay tax on the profit they earn.

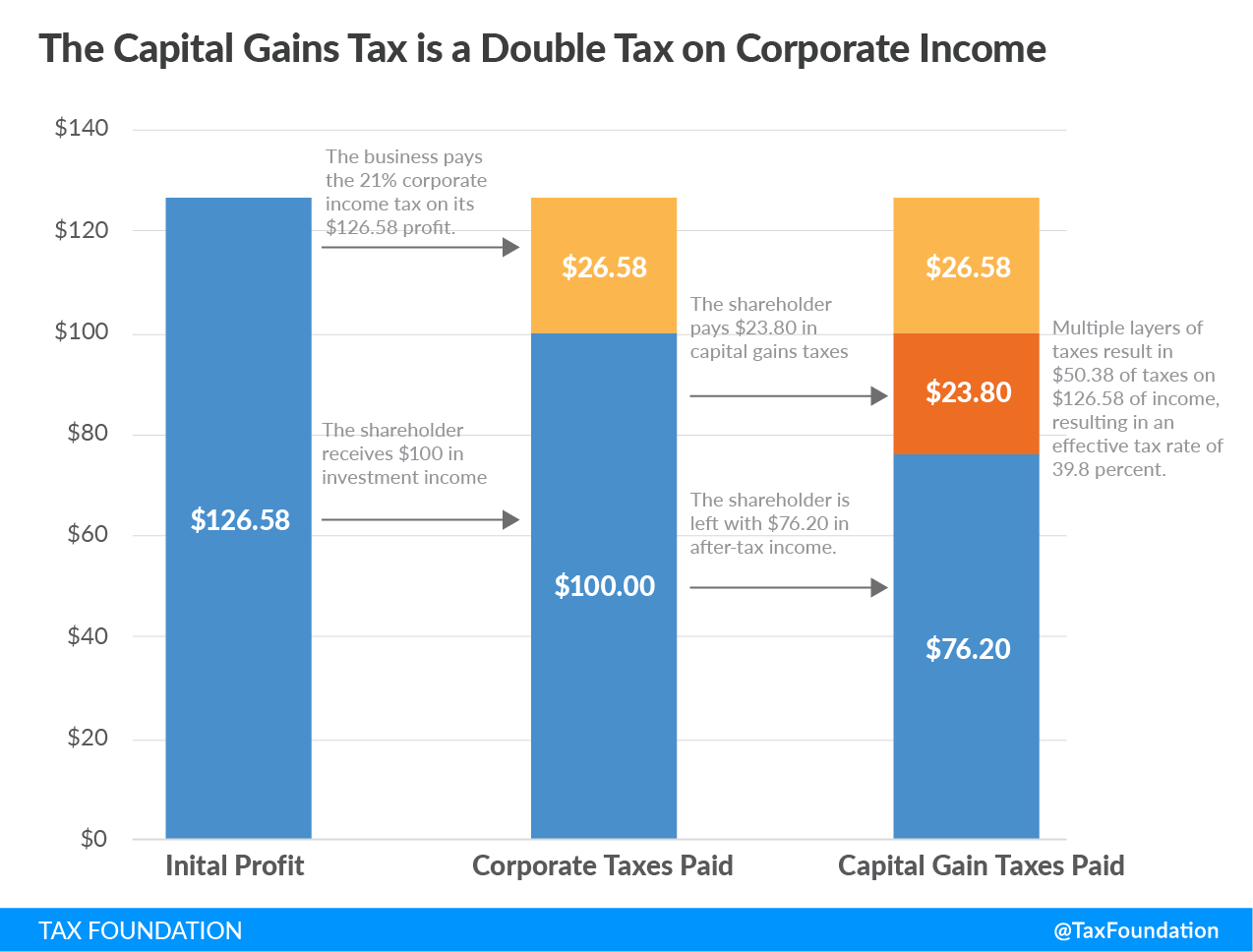

When applied to profits earned from stocks, capital gains taxes result in the same dollar being taxed twice, also known as double taxation. That's because corporate earnings are already subject to the corporate income tax.

Taxes on What You Buy

Sales Taxes

Sales taxes are a form of consumption tax levied on retail sales of goods and services. If you live in the U.S., you are likely familiar with the sales tax from having seen it printed at the bottom of store receipts.

The U.S. is one of the few industrialized countries that still relies on traditional retail sales taxes, which are a significant source of state and local revenue. All U.S. states other than Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon collect statewide sales taxes, as do localities in 38 states.

Sales tax rates can have a significant impact on where consumers choose to shop, but the sales tax base—what is and is not subject to sales tax—also matters. Tax experts recommend that sales taxes apply to all goods and services that consumers purchase but not to those that businesses purchase when producing their own goods.

Gross Receipts Taxes

Gross receipts taxes (GRTs) are applied to a company's gross sales, regardless of profitability and without deductions for business expenses. This is a key difference from other taxes businesses pay, such as those based on profits or net income, like a corporate income tax, or final consumption, like a well-constructed sales tax.

Because GRTs are imposed at each stage in the production chain, they result in "tax pyramiding," where the tax burden multiplies throughout the production chain and is eventually passed on to consumers.

GRTs are particularly harmful for startups, which post losses in early years, and businesses with long production chains. Despite being dismissed for decades as inefficient and unsound tax policy, policymakers have recently begun considering GRTs again as they seek new revenue streams.

Value-Added Taxes

A Value-Added Tax (VAT) is a consumption tax assessed on the value added in each production stage of a good or service.

Each business along the production chain is required to pay a VAT on the value of the produced good/service at that stage, with the VAT previously paid for that good/service being deductible at each step.

The final consumer, however, pays the VAT without being able to deduct the previously paid VAT, making it a tax on final consumption. This system ensures that only final consumption can be taxed under a VAT, avoiding tax pyramiding.

More than 140 countries worldwide and all OECD countries except the United States levy a VAT, making it a significant revenue source and the most common form of consumption taxation globally.

Excise Taxes

Excise taxes are taxes imposed on a specific good or activity, usually in addition to a broad consumption tax, and comprise a relatively small and volatile share of total tax collections. Common examples of excise taxes include those on cigarettes, alcohol, soda, gasoline, and betting.

Excise taxes can be employed as "sin" taxes, to offset externalities. An externality is a harmful side effect or consequence not reflected in the cost of something. For instance, governments may place a special tax on cigarettes in hopes of reducing consumption and associated health-care costs, or an additional tax on carbon to curb pollution.

Excise taxes can also be employed as user fees. A good example of this is the gas tax. The amount of gas a driver purchases generally reflects their contribution to traffic congestion and road wear-and-tear. Taxing this purchase effectively puts a price on using public roads.

Taxes on Things You Own

Property Taxes

Property taxes are primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings and are an essential source of revenue for state and local governments in the U.S.

Property taxes in the U.S. account for over 30 percent of total state and local tax collections and over 70 percent of total local tax collections. Local governments rely on property tax revenue to fund public services like schools, roads, police and fire departments, and emergency medical services.

While most people are familiar with residential property taxes on land and structures, known as "real" property taxes, many states also tax "tangible personal property" (TPP), such as vehicles and equipment owned by individuals and businesses.

Overall, taxes on real property are relatively stable, neutral, and transparent, whereas taxes on tangible personal property are more problematic.

Tangible Personal Property (TPP) Taxes

Tangible personal property (TPP) is property that can be moved or touched, such as business equipment, machinery, inventory, furniture, and automobiles.

Taxes on TPP make up a small share of total state and local tax collections, but are complex, creating high compliance costs; are nonneutral, favoring some industries over others; and distort investment decisions.

TPP taxes place a burden on many of the assets businesses use to grow and become more productive, such as machinery and equipment. By making ownership of these assets more expensive, TPP taxes discourage new investment and have a negative impact on economic growth overall. As of 2019, 43 states taxed tangible personal property.

Estate and Inheritance Taxes

Both estate and inheritance taxes are imposed on the value of an individual's property at the time of their death. While estate taxes are paid by the estate itself, before assets are distributed to heirs, inheritance taxes are paid by those who inherit property. Both taxes are usually paired with a "gift tax" so that they cannot be avoided by transferring the property prior to death.

Estate and inheritance taxes are poor economic policy because they fall almost exclusively on a country or state's "capital stock"—the accumulated wealth that makes it richer and more productive as a whole—thus discouraging investment.

Both taxes are also complex, hard for jurisdictions to administer, and can incentivize high-net-worth individuals to either engage in economically inefficient estate planning or leave a state or country altogether.

For these reasons, most U.S. states have moved away from estate and inheritance taxes.

Wealth Taxes

Wealth taxes are typically imposed annually on an individual's net wealth (total assets, minus any debts owed) above a certain threshold.

For example, a person with $2.5 million in wealth and $500,000 in debt would have a net wealth of $2 million. If a wealth tax applies to all wealth above $1 million, then under a 5 percent wealth tax the individual would owe $50,000 in taxes.

As of 2019, only six countries in Europe—Norway, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Italy—had a wealth tax and two of those—the Netherlands and Italy—raised no revenue from it (see chart below). Countries have repealed their wealth taxes because they're difficult to administer, raise relatively little revenue, and can have harmful effects on the economy, including discouraging entrepreneurship and innovation.

Pay as You Earn Taxation Economics Definition

Source: https://taxfoundation.org/the-three-basic-tax-types/

0 Response to "Pay as You Earn Taxation Economics Definition"

Post a Comment